In conversation with

Martin Pousson

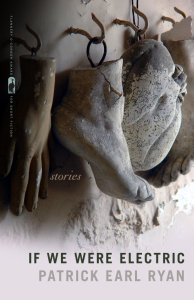

Patrick Earl Ryan discussed If We Were Electric with Martin Pousson, hosted by Kar Johnson of San Francisco’s Green Apple Books.

- Kar

I’d like to go ahead and introduce our authors for the evening. Martin Pousson was born and raised in the Cajun bayou land of Louisiana. His novel Black Sheep Boy, a novel in stories, won the PEN Center USA Fiction Award and the National Endowment for the Arts fellowship, and it was featured on NPR’s The Reading Life and as a Los Angeles Times literary pick and as a Book Riots Must-Read Indie Press Book. No Place, Louisiana, his first novel, was a finalist for the John Gardner Fiction Book Award, and Sugar, his book of poems, was a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award for gay poetry. He is a professor of creative writing and queer studies at Cal State Northridge. It’s my pleasure to welcome Martin Pousson… and…

Patrick Earl Ryan was born and raised in New Orleans, Louisiana. His work has appeared in the Ontario Review, Pleiades, Best New American Voices, San Francisco Bay Guardian, Men on Men: Best New Gay Fiction for the Millennium, Cairn, and the James White Review. Founder and editor in chief of Lodestar Quarterly, Ryan has also taught martial arts philosophy and tai chi chuan for many years. He lives in San Francisco… and his debut story collection If We Were Electric is the reason we are here this evening. Please join me in welcoming Patrick Earl Ryan.

- Patrick

I think we’re on, do we start?

- Martin

I think so, we’re on now. All right. How you makin’, Patrick?

- Patrick

I’m makin’ just fine, just fine.

- Martin

’Cause you know that’s how we say it in New Orleans, “how you makin’?” I think it’s an exciting moment to be right here at the start of your publishing career. And it’s a thrilling book. Congratulations on the Flannery O’Connor Prize. That is extraordinary and very well deserved. As you probably know, we have a couple of dirty jokes about Flannery in Southern Louisiana. Often we riff on the title of her most famous story “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” so it’s “A Hard Man is Good to Find,” right? And that’s probably what Evie thought in your story, “Before Las Blancas.”

- Patrick

[laughs] True!

- Martin

I really do wanna just throw all the praise I can on you. I think it’s a riveting collection. They’re exciting stories. Even though many of them were written as long ago as the late 90s and early 00s, it feels utterly contemporary. I feel like time is collapsed in this collection, and it’s remarkable that you achieve that effect, and we may talk about that a little bit…

So Patrick, what’s your mama and daddy’s name? And can your mama make a roux?

- Patrick

I’m named after my mom and my dad both. I was the last of five sons, so I was named Patrick after my mom Patricia, and my middle name is Earl, which was my dad’s name. I’m their fifth child, although I’m my dad’s eighth child because my dad was married six times. I turned out exactly the way I should because of that history!

You know my mom can make a pretty good roux, but I have to say I make a better roux than my mama!

- Martin

Ooooo that’s dangerous talk, now. All right, now we know this because we’re from Southern Louisiana, but neither one of us are actually white, as in American white, Anglo-white, right? I’m Cajun, you’re Creole. For those who don’t know, would you tell us a little something about Creole, being Creole, what is that?

- Patrick

A lot of people think that Cajun and Creole are the same thing, which is not the case, although I do have a bit of Cajun blood on my mom’s side of the family, Acadians who came down from Quebec in the mid-1700s and went to Plaquemines Parish. My dad’s side, what he used to identify as a Heinz 57 background, is descended from five different continents. A Creole in the strictest sense, back in the beginnings of New Orleans, would be anyone who was born in New Orleans and was a mix of the various cultures, French, Spanish, Native American, Black blood. As it progressed, the French bought out the Spanish, so it came to be known as the French-speaking area of New Orleans, to the east of Canal Street, or later to the east of Esplanade Avenue. That Faubourg Marigny neighborhood was one of the largest Creole neighborhoods of New Orleans. Throw whatever you want in there. It’s kind of like a jambalaya, you know, that’s what it is, Creole.

- Martin

That’s right… or a good gumbo, right? The fact that you have some Cajun in you just elevated you in my mind. Many people don’t know that part of this heritage that you’re talking about has to do with the fact that there were free people of color decades before the Civil War in New Orleans, and the third neighborhood to form in the city, the Treme, was populated with gens de couleur libres.

You season your stories with some French, which reminds me that, as a Tulane historian said in Louisiana, French is not a foreign language. If Juno Diaz can talk about Spanglish in Oscar Wao, then you can talk about Franglais in your book. There are a lot of terms that come at us in your stories, so just a couple of them… what is a peeshwank?

- Patrick

[Laughter] Now that is more of a Cajun term, isn’t it? Do you know that term? I’m gonna defer to you on what the exact definition is, but it’s like calling somebody something cute, something you would call a little child…

- Martin

Right. Like, that little cute thing off to the side…

- Patrick

A term of endearment.

- Martin

Also feux follet, which is not just a word in a story, but the title of a story. What is that?

- Patrick

I’m very interested in folklore. I’m also interested in voodoo, though not necessarily in practicing voodoo, but how we grow up in New Orleans and have voodoo surrounding us. It becomes part of our vocabulary without us even knowing its real details. Now, feux follet are these mysterious little lights that you would see out in the woods with fortune attached to them. You might see them out in the swamps. They’re magical lights. When I was young, I would go out to the woods in Mississippi to trip on acid and get drunk. Sometimes I’d see fireflies out there and I’d wonder if that’s where this idea started…

- Martin

There you go. The dull answer is that it’s phosphorescence. That’s the dull, scientific answer, and the bayou not only has phosphorescence, but you throw in oil and everything else from the environment… right? But really, what Creoles and Cajuns think is that feux follet are little sprites or elves, or more to the point… fairies that are at the perimeter of our vision and sparkling magically for us… So… speaking of sparkling magically, you mentioned voodoo, I will just show everyone that I’m casting a little voodoo for you and the great success of If We Were Electric now, and to further add to the voodoo, I’m hoping you might be willing to read a little something to give us a taste, a little flavor of the book.

- Patrick

I would love to! I’ve been thinking about what I should read and because I haven’t had the chance to read from the title story, I thought I’d read just the first couple of pages from that. Not too much, just to give a sense of the language of the book. Kar, you had mentioned earlier that it’s a great autumn or fall read, but I really think of the book as a summer book. I think there’s so much heat, and this is a good example of that… thunderstorms… humidity… this is the title story, If We Were Electric.

It’s by the Royal Street Grocery, walking in warm and fat rain, when I first see the boy named Mark. He'll take away more than one thing in my life. How many times had I walked this exact street wishing for some thing similar? I’m spending the day looking for books. In the back of my mind I’m looking for men—I’m still a virgin at twenty-one.

He waits on top of a blue city garbage can, long legs beating against metal, drinking straw hung from his bottom lip. He’s looking for men, too. A man, a French sailor with short legs in full uniform, struts out of the grocery’s white swinging doors, and Mark, although I don’t know his name yet, is vying for attention. He keeps the sailor within hungry eyes, enough for me to recognize lust and begin to possess it myself: a low shake inside the gut when he opens his legs wider, pulling his red shorts away from skin, revealing the bare white of his inner thigh. He’s pure grit. But the sailor is daydreaming of other things: Nimes, a woman in Paris, his ship.

I’m counting money or pretending I am; my head down even while my eyes are up. If I keep walking I won’t talk to him. If I stop then I’ll be at a loss for words. We are both adolescents, in some respects, lacking adult candor. But it will work itself out, I decide. It’s a must do. Out of the nickels and quarters, he is a blooming face—fierce eyes, lips that could bite back, and scar above his right cheek—rising out of my palm. I am in love with him like this.

Here—while I’m wishing—the sailor pulls an umbrella from the grocery bag and opens it. Then off he dashes down Royal Street. Mark, the still nameless conspiracy of bumbling limbs that he is, lops down from the top of the garbage can more gracefully than I ever could and stands, a monument in the middle of the sidewalk, gazing at the sailor one final time—a departing blue figure in misty rainfall.

Women and men pass and bump the boy out of their way. I walk up behind him and the dark-haired, randy boy who will be Mark turns to me, pulls the straw out of his mouth, and smiles big, white teeth everywhere. “Don’t worry—I’m used to this kinda weather,” he tells me, and just as quick, turns and follows his oblivious sailor.

I’ll stop there.

- Martin

I’m so glad you read that part because it’s so hot, right? You talk about heat and temperature, but the stories are also just so sensual. So much of the writing is incredibly sensual. In thinking about the book as a whole, I was imagining as it would be taught, someone might think of these stories as experimental, but I don’t think they’re experimental, because if they’re experiments they succeed brilliantly. I don’t think of them as experimental so much as unconventional, but then they’re only unconventional if we think about American storytelling, which is based on rationalist, Calvinist, Protestant problem/solution axes. Yours don’t work that way. They run counter that. The stories are almost inevitably fragmented in structure. There’s ample use of ruptures and white space and glyphs to separate these fragmented episodes. Yet the collection holds together as exactly that… it’s a collective experience of a myriad of characters through an expansive time with a coherent voice and a coherent purpose. The boundaries in this book I thought were interesting because they’re not about boundaries of state or city or parish or race so much as they are boundaries of… they’re not even boundaries of the body… they’re boundaries of the mind. The coherence seems to arise out of a kind of psychological probity, and it seemed to me your aim was to put forward these seriously flawed people who are both flawed and yet perfect. There’s an incredible amount of hard mercy and tough grace in these stories. As a whole, they shouldn’t work, these stories, but they do. There’s little to no plot. There’s often no cause and effect with some sort of logical motivation. There’re often no clear antagonists, unless it’s a hurricane. The stories are not interlocking. They don’t share a narrator. There’s no single protagonist or point of view. They don’t always share a theme. But they always share a setting. In one way or another, the stories arise out of an escape from or a return to New Orleans, so the collection ends up being almost like a travelogue… which seems ideal for your readers who are trapped in their homes right now, want to get out, and want to go somewhere new and utterly different. That’s what you offer, Patrick. It’s utterly distinct. It’s utterly New Orleans. It’s redolent with the place. I wanted to know, as a seventh-generation New Orleanian, was this your strategy? Did you decide you were writing a whole collection that would be interconnected in one way only—New Orleans? Or is New Orleans just that bitch that commanded you to write only about her? Which is it?

- Patrick

I would have a hard time separating those two, because I think they’re both true. I will say that there are quite a number of influences in the book, literary influences, and one of the obvious ones when I look at the story collection on a whole would be James Joyce’s Dubliners, in the sense that he is taking a city and showing that this is the effect, this is the power of the city on its people. This was also what I wanted to convey in the book, that there is a power that New Orleans exerts upon its citizens. So even when you have the narrator in “I Wouldn’t Say No,” who is in London, there is still this magnetism that is pulling him back to New Orleans. It’s the swamp dragging you down into its mud, into its dirt. Personally, it was difficult for me to get out of New Orleans, even though now I just want to go right back. It’s that draw and pull and push that keeps happening. New Orleans itself is what spoke… or I shouldn’t say spoke, but yelled for me to write this book and to write it in that way. New Orleans is the connection between each of these stories. The title itself, If We Were Electric, speaks a little bit of that, what’s connecting everything. It’s the electricity that the city itself possesses, that pulls and keeps everything together.

- Martin

Your adoration for the place is intoxicating and utterly seductive, and yet you live in San Francisco. Do you think that distance is part of what infuses and empowers your storytelling about a place in which you don’t currently live?

- Patrick

I think that it is. All of the stories were written outside of New Orleans, so they were written once I had come to San Francisco. In a way, they are representative of my yearning for New Orleans. They were a way of me possessing the city without being able to live there. I would live there. I would love to live there, but life brings us to different places, and we just have to do what we can to get by, to live. It’s a difficult city… bearing the weather, for example. So I think that this was my way of remaining a New Orleanian. I do have a deep love for the city, and I do go back. I haven’t been able to go back this year, but in the past I would go back every year. It refuels me. I’ve spoken about this before, that I’m an introvert, which is odd for a New Orleanian, but I think it’s because I live out here in California. Every time I go back to New Orleans, as soon as I step foot off of the airplane, as soon as I get into a cab or an Uber, I’m completely an extrovert again, my voice comes back, I’m in love with the city, and it comes out of all my pores… did I get off point?

- Martin

No, no no… you’re right on point. What you’re saying is people there speak the language, right? We share a language. Like a couple of raccoons, when we were first introduced to each other via email, we had to root around in each other’s garbage, and we discovered that we near missed each other in New Orleans, in Lafayette, but also in San Francisco by just a couple of years.

There are a lot of surprises in this collection, and one of the surprises is that although there’s this utter fascination with New Orleans, the stories are populated with people who aren’t always from New Orleans or even from the U.S. You mentioned London, but you also have Chinese, Japanese, Czech, New Zealander characters. I wondered, was that part of a strategy? New Orleans is often thought of as the exemplum primi of regionalism and parochialism, but anyone who knows New Orleans knows that it’s incredibly international, and it once vied with New York for European capital of the West. Were you pushing against that parochial view of the city by purposely populating your stories with people who were from other places or other backgrounds?

- Patrick

I don’t know if it was completely conscious as I was writing them, but as they were written and finished, and I started looking at them as a whole, I certainly saw that, and I understood it as something that I genuinely believed about my city. Growing up I would always think of New Orleans as completely separate from the South. This isn’t the South. We’re not the South in New Orleans. Y’all are the South. We’re this little European city that’s tucked away from everyone else around us. If you look at even just voting records, how people vote in Louisiana, you have the entire state basically red, but then you have New Orleans and it’s blue. So there is this internationalism. It’s always been that way. It was the third largest city in America during the 1800s, and if not the richest then one of the richest cities. People came from all over. Myself as an example of what New Orleans is… I was saying earlier my ancestors came from five continents. One lineage from my dad’s maternal side is from Filipino boat jumpers who escaped from the Spanish armada ships in the 18th and 19th century and became shrimpers in Barataria Bay, which is to the east of New Orleans. I have four brothers. They’re all straight. One of my brothers married a Cambodian immigrant who came to New Orleans in the early 1970s. She was a refugee. There’s also a large Vietnamese community in New Orleans East. I grew up seeing Asians. They were close to my family, close to the Creole culture. It wasn’t anything strange to see people from all over the world in New Orleans. I think that makes it so different than the rest of the South.

- Martin

The streetcar always seemed to have a great desegregating effect on the city. You know, it was the first city in the U.S. with an opera house, the first apartment building, first public bar, and some even say first public gay bar with the original Lafitte’s. So I’m glad you mentioned your straight brothers because one of the many surprises in this book is that although the book is mostly homosocial, concerned with men and boys mostly behaving badly, it’s not homosexual, not explicitly. There’s a big embrace here of all masculinity, liminal masculinity and otherwise, and readers might be surprised, for example, to know that the story that is most explicitly concerned with HIV/AIDS features a straight character who has HIV/AIDS. Also, I thought it interesting to go back and look at the beginnings of the stories. All but two of them work along these lines. These are the first sentences, for the most part… we have “I could smell him,” then “So I punched him square in the nose,” “During his nighttime walk,” “My brother’s ghost,” “I’m in love with Kent,” “Three men lived in the last house,” “He wasn’t the sort to keep secrets,” “I first see the boy named Mark,” “I haven’t told you about my real brother,” and finally, “He expected a thunder’s mighty rumble.” So when I looked back at the collection as a whole, I started wondering, in addition to making the stories populated with this international view of the city, were you also trying to really hone in and focus on what it means to be male and masculine in a place like New Orleans, which is completely distinct from being male and masculine in the rest of the country?

- Patrick

This is reflective of my own personal history, growing up with four brothers, no sisters. My mother was my only feminine role model, my only feminine connection. I went to a Catholic school for grammar school and high school. My high school was all-boys, so my connection with the world was through a masculine lens. I didn’t have close friends who were female. I have friends now who accuse me of being afraid of women, which I’m not, it’s just who you have around you become the friends that you have. It is personal experience. That’s why it’s so focused on the masculine. This collection represents a particular decade for me. That decade was obsessed with masculinity, obsessed with men, the crushes that I had, the straight masculinity in my family.

- Martin

I should make clear that your book has such a wide embrace that women are there, it’s just that men are the anchor, men are the protagonists invariably. But the book does start with a boy trying to leave his mother and then it ends with a man trying to in one way or another return to his female friend. I’ve often thought about the fact that our culture really is almost more matriarchal than it is patriarchal, so I wonder if that’s why sometimes we feel contested in our gender roles. It’s a fascinating part of the book, and I admired it. I also really admired the superstructure, because again, in a book that doesn’t have more of the obvious interlocking, interconnected points, it’s evident that you really thought about how to arrange and sequence it all so that it would have a totalizing effect. When I reached the last story and we had the mandatory evacuation in “The Tempest,” for an approaching hurricane, it led me back to the beginning, and in “Before Las Blancas,” you’ve got two men, or a man and a boy, who are driving down a hurricane evacuation route away from New Orleans. Then it ends with a man answering the call of a woman and pondering how long to New Orleans by canoe or by foot… of course I thought of Fats Domino’s “Walking to New Orleans.” You’ve got in the beginning fat mosquitoes and singing locusts and the Atchafalaya swamp, then in the end you’ve got this overgrown flooded swamp… it starts with the smell of semen and ends with the sight of blood, so it seems…

- Patrick

Well, I don’t necessarily say it’s semen…

- Martin

No, no. But I figured that out on my own. [Laughter]

It ends up having this incredible superstructure, so I wondered to what degree when you started putting together all these stories did you intend that effect, and if so, what then was the strategy? What are you trying to say to us about the experience of all these men in New Orleans?

- Patrick

I think that the structure is subtle. It was purposeful, but it was subtle. I spent a lot of time seeing how I liked the stories arranged. For example, in a very obvious way I start with “Before Las Blancas” because it is the youngest narrator of the collection. It’s this flowering, this birth, the springtime coming out of the ground, his awakening. I also like the idea of mirroring. For example, the story “The Blue Son,” which is the story of a mother and two brothers, mirrors “Where It Takes Us,” which says, so this is the story of my real brother, “I haven’t told you about my real brother.” It’s almost as if the narrator of the entire collection is saying, “Oh, I’m a storyteller, and I was telling you a fib before, but this is the real version,” and of course neither is the actual real version… and it was important for me to have those mirrored stories spaced apart from each other so that you had a chance to notice that reflection. If they were right next to each other that would be too obvious. I want that to come to the reader in a more natural way rather than being pushed into their face. Cars are also very important throughout the entire collection, cars breaking down, and in one story a car passes on the roadway, which is the same car that is in another story. Even though the stories may seem very disjointed and disconnected, they do rope through each other in subtle ways.

- Martin

New Orleans is a city of masking, and one part of the beauty of your book is that it’s never overt, it’s never direct, it’s never didactic. Its spaces are always changing. It’s subtle, but it’s also wonderfully arcane and mysterious. So I only come to these conclusions because I have to sit there and reflect on it. It’s not that you’re broadcasting all this. I think that’s part of the power of the writing. You allow us to do some of that work. In Southern fiction, especially Southern Louisiana, place is always the shadow protagonist, and if place is the shadow protagonist, then memory is the antagonist, because nothing marks place or spikes it more than the smell of it. Your book has so much of the funky aura of New Orleans and seemed to be a way to gin up memory and have that memory clashing with place, and the stories spin out of that. I think it’s fantastic.

- Patrick

Is that not the way the rest of the world is?

- Martin

No, no, it’s only New Orleans! You mentioned possession earlier, and I was interested also in the fact that these stories are usually in one way or another about severance, about death, but not death the way that would be understood in the rest of the nation, not an Anglo sense of death as permanent. Instead you have a lot of living death. You have a lot of ghosts. So I wondered if you’d say a little something about the dual meaning of possession in New Orleans, because it’s not a single meaning there, right?

- Patrick

Right. The stories that come to mind… “Feux Follet,” that’s a good example, and that is right next to “The Blue Son,” both of those deal with this idea of possession and death and spirit. The mother in “The Blue Son” is so overcome with grief, she refuses to allow the memory of her son who has died to leave. His ghost then possesses the entire house. In the same way, in “Feux Follet” you have the old man who has lost his daughter and that memory possesses him. So memory as a way of possession. In a larger sense, you look at New Orleans and how the city itself possesses the people who live there. There’s such a history with New Orleans, such a diverse history, that it possesses you, too. I was very interested in examining that and how people can’t get away from those spirits, from those ghosts that haunt them even though time has passed.

- Martin

The possessions also are sometimes sexual. One of the elements that really fascinated me with this book was the way in which everyone ultimately is forgiven, but it doesn’t even feel like forgiveness is called for, because there’s such an embrace of these characters, and such an overwhelming sense of affection for them all coming from the narrator, who ultimately is you. You mentioned that it’s sometimes autobiographical, and I thought of how powerful it is… fiction. It’s not rhetoric, it’s not about persuasion, it’s more of an art of seduction, and you’re so incredibly seductive that when we read the first story, we might forget that it’s a romance of a 13-year-old boy and a 28-year-old man, but we don’t think of words like pederasty. There’s no sense of indictment or crime, although this would be a criminal act in really every state in the country. I felt like you really worked to have us so seduced with this world and these characters that we dropped our usual moral framing and instead adopt a more truly moral framing, and that is an awareness and awakening to the fact that if you’re truly alive, if you’re truly breathing and smelling and sensing, then you are always fucking up, you are always behaving badly, but each bad step is a step that moves you forward. In this book we’re always moving forward… ultimately to grace. There’s always feux follet. There’s always light at the end in your stories. The plots are sinewy, they’re forked like all the little waterways around New Orleans, but there’s often this burst like a coronary system. There are passages that even have the fierce familiar grip of a tender heart. That’s the ultimate triumph of this book, that through all of the murk and mud and mystery of New Orleans, at the end what you really deliver is an incredibly light, powerful, and majestic sense of what it means to be human in a place as topsy-turvy as New Orleans. Right now, in this country, we’re all living in a topsy-turvy place, so you really offer all of us this chance at redemption.

- Patrick

Yes. And you’re always forgiven. There’s that sense of always being forgiven. It’s a tricky business when you’re dealing with pedophilia, and that would be a completely different story, of course, if it was told from Neil’s adult point of view. But it’s Evie’s point of view, and what we have instead is… we all know what it feels like to be in love, we all know what it feels like to long for something, to desire something, so the story keeps its bearings by focusing on those primal emotions that he’s having, that desire that he’s having. Desire is something that winds throughout the entire book. Not always sexual desire.

- Martin

Yes, and if we are not to behave badly and if we’re to be forgiven by Kar, we should turn this over to your readers and your fans for some questions…

- Kar

I encourage you both to behave badly, please. We do have a couple of questions. Mike asks, at the end of “The Cargo,” did you get much pushback about the point of view shift in its final paragraphs?

- Patrick

"The Cargo” didn’t always end the way that it ends in the book. Initially there was a point of view change where we switch from the point of view we’ve had for the entire story, Hank, to the wedding singer at the end. At the end now, my intention was that this is reincarnation. What happens at the end is the boy dies, but then there’s a rebirth. He is born, and he sees the lights of the hospital room, and he’s taken into his mother’s arms. That felt more in line with the rest of the book, that idea of forgiveness, that idea of redemption. And that’s a rough story. There’s a lot of violence in that story. I’m very interested in that like Flannery O’Connor. We can even look at “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” as well as a Paul Bowles story, “The Delicate Prey,” about two uncles traveling through the desert with their nephew who get murdered by another tribe, and the boy is castrated and his penis is stuffed into his stomach. That’s Paul Bowles. I guess he was smoking a lot of pot at the time, too. But “The Cargo” is playing off of both of those stories, and instead of having it be… say with Flannery O’Connor, this sort of idea of judgment at the end… I wanted that idea of redemption instead, forgiveness at the end, the light coming through…

- Kar

Thank you. One more question about the design of the cover of your book. This is St. Roch, yes?

- Patrick

Yes, St. Roch Cemetery. That’s the Chapel of Prosthetics at St. Roch Cemetery. That is also, coincidentally, where my dad and my grandparents are buried, which the person who designed the book cover did not know. That they found this photograph and were like… what do you think of this? I was like, wow, do you realize what you’ve just done?

- Kar

What fate, what kismet! That’s so interesting because I’m concerned with books as objects, and I do think design is important. I think we should judge books by their cover because books should be designed beautifully. So in thinking of the kind of disembodied pieces and the embodied pieces happening at the same time, and that this is a story collection, I just thought it was so brilliant. I was wondering if that was a concern going in, if it was a form and function thing, but to hear your answer now, that it also has a personal connection to you…

- Patrick

It does. It’s a personal connection, and you know, I had a great fear going into this because I didn’t have control over the cover. I didn’t know what was going to happen. I didn’t know if I was going to wind up with a male torso on my cover, which I was hoping wouldn’t happen. It was beautiful to see this. It took my breath away. It brought back so many memories, because my dad died when I was 15, my grandparents died before I was born, and the way that I got to know my grandparents was to go to the cemetery and visit the graves. We would go every year, the day after Halloween, to bring flowers… All Souls’ Day, or All Saints Day… so that’s how I knew them, actually visiting the ground where they were buried. This was remarkable to see this cover happen. The book was also released on what would have been my dad’s 109th birthday, September 15th, which wasn’t my doing, either. It was just the way the universe spoke…

- Kar

That’s beautiful. That’s fate. That’s lovely. You can’t write that.

- Patrick

Kar, thank you so much for inviting me to have this event. It was lovely. Martin, of course, thank you. It’s really nice to have an event with another Louisiana boy. When do we get a chance to do that? It’s rare to have us both in the same room.

- Martin

There you go, as seductive in life as you are in your fiction. Thank you, Patrick, for writing this book. I encourage everybody, if you haven’t already picked it up, here’s the thing… you look at this cover, and if you’ve ever been to New Orleans, or if you’re from there… it’s this tiny low-ceiling little shrine with these fragments of human bodies hanging down. These are all blessed parts, people praying for a heart to be healed or a foot to be healed. That’s what your book really is about! If you can’t make it to New Orleans, if you’re trapped in your house during the time of COVID, you can go there by picking up a copy of this book and reading these stories. It was a trip for me in every sense of the word. So I thank you, Patrick, and I thank you, Kar, for inviting me to join this unholy trinity here.

Buy the books

Video

(Visit online for the video section.)

If We Were Electric

If We Were Electric Black Sheep Boy

Black Sheep Boy No Place, Louisiana

No Place, Louisiana A Good Man Is Hard to Find and Other Stories

A Good Man Is Hard to Find and Other Stories Dubliners

Dubliners The Delicate Prey and Other Stories

The Delicate Prey and Other Stories